Gravitational waves and neutron stars (outreach)

(Article originally written for the University of the Balearic Islands 1st outreach competition in 2020, slightly modified here)

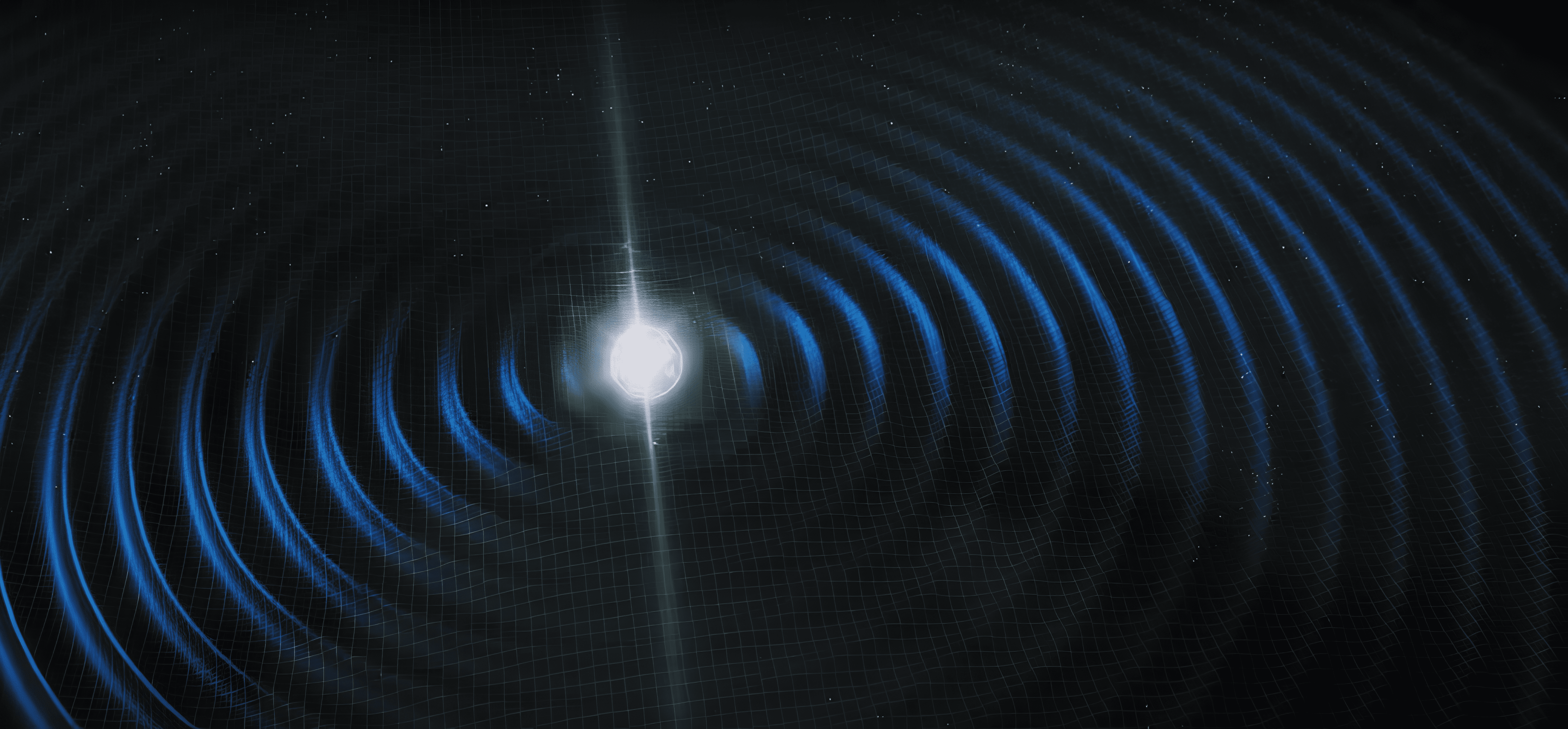

In September 2015, the first direct detection of gravitational waves (GWs) from a collision of two black holes took place. When we talk about waves, we talk about a disturbance that moves at a certain speed of the state of a medium (like air or water). For example, when we throw a stone into a lake, the level of the water surface changes and this is transmitted around the point where the disturbance originated. GWs are generated whenever a distribution of mass or energy is accelerated, and in this case the medium that is disturbed is space-time itself: distances and time intervals that we measure are affected by the passage of these waves. The amplitude of GWs is so small that with the detectors that currently exist on Earth we can only detect the waves created by objects as compact and energetic as black holes or neutron stars.

Neutron stars are the remnants that are left after a supernova explosion of stars with masses between 8 and 30 times that of the Sun. Neutron stars are very interesting objects, since due to their radius (around 12 km) and their mass (between 1.4 and 2 times the mass of the Sun) the density at their center is greater than the density at the atomic nuclei. The behavior of matter at such high densities is not yet known since these extreme values cannot be reached in terrestrial laboratories, and that is why these stars represent cosmic laboratories that provide us with unique opportunities to expand our knowledge of matter. In addition to their high density, neutron stars possess the greatest magnetic fields in the Universe, and can be rotating at very high speeds: the neutron star with the highest rotational speed spins 716 times every second!

In 2017, the first gravitational wave from a collision of two neutron stars was observed. This detection represented the birth of the so-called multi-messenger astronomy, since in addition to gravitational waves it was also possible to detect the emission of electromagnetic waves (from radio waves to energetic gamma rays) coming from this merger.

So far, all gravitational waves that have been detected are of the transient type: since before the collision we can only detect a small number of orbital periods, the detected signal has an approximate duration of seconds or minutes at most. Another type of gravitational waves that have not yet been detected but are regularly searched for are the so-called continuous gravitational waves (CWs). While transient waves are short-lived, CWs are virtually infinite. These waves can also be produced by neutron stars: as they rotate, they will emit CWs if they have an asymmetry around their axis of rotation.

Why haven't we detected CWs yet? In a collision between two compact objects, more energy is present and, moreover, it is released in a more sudden way, while continuous waves are emitted by processes that are not as catastrophic as such collisions. Because of this difference, CWs have an even smaller amplitude and are much harder to detect. On the other hand, since its duration is practically infinite, we can collect data during longer time intervals and analyze it together, which increases the possibilities of detection (but also makes these searches more demanding from a computational point of view).

Although no continuous wave has been detected so far, multiple searches have been carried out that allow us to calculate upper limits to the asymmetry that neutron stars in our Galaxy possess. The most recent results from searches of CWs produced by unknown neutron stars provide limits as low as one part in one million (for neutron stars at 100 parsecs rotating at 100 Hz), which means (for a star of approximately 12 km radius) that there is no asymmetry around the rotation axis of more than 12 millimeters: if this asymmetry was greater we would have already detected the GWs that would have been produced!

In addition to understanding black holes and neutron stars, detections of gravitational waves (both transient and continuous) can also help us to discern whether General Relativity is the correct description of gravity. Due to several factors, such as the predicted singularities at the centers of black holes, we know that General Relativity is a theory that is not complete. Several alternative theories that make different predictions have been developed, and by means of gravitational waves we can compare these theories and see which one best fits the obtained data. An example is the speed of gravitational waves: General Relativity predicts that they travel at the same speed as light, but other theories argue that this might not be the case.

Through both detections of transient and continuous gravitational waves we hope to learn much more about the behavior of matter in extreme environments and about the correct description of gravity. Gravitational-wave astronomy has only just begun, and many surprises and new discoveries await us in the coming years!

For a more visual introduction to CWs, there is this video produced by the continuous gravitational waves group at the Albert Einstein Institute.